back to decision-makers list

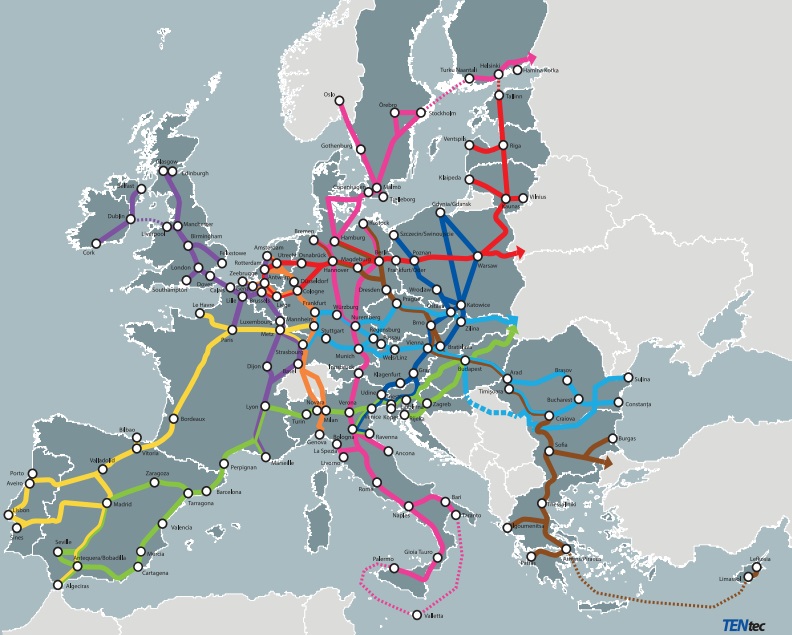

The UK traded £134 billion worth of goods to the rest of the EU in 2015 and the EU traded £223 billion to the UK. Not all of this passes through the Calais-Dover route, but a significant amount of it does. The trade passing through the Port of Calais is estimated at around £90 billion a year, while the trade passing through the Eurotunnel is roughly the same, at some £91.4 billion. The TEN-T (Trans-European Transport Networks) policy of the European Union has devoted billions of Euros to its aims of “[closing] the gaps between Member States’ transport networks, [removing] bottlenecks that still hamper the smooth functioning of the internal market and [overcoming] technical barriers such as incompatible standards for railway traffic.” The Calais region has been a major beneficiary of this funding, which covers part of the cost of Calais’ port expansions, rail terminals and other infrastructure. In the TEN-T map of ‘core network corridors’, the Calais-Dover route is the only key route depicted as connecting Ireland and the UK to ‘Schengen Space’. As a crucial link in the trade network, bottlenecking at the Calais-Dover route has a significant potential to create blockages to the idealized smooth flow of trade across these corridors.

Image: The Calais-Dover route is the only connection between the UK and Europe shown in the trans-European transport network (TEN-T) ‘core network corridors’ map

Internal structures

Probably hundreds of individual logistics companies pass through Calais. Some are represented by trade associations such as the:

-

Freight Transport Association (FTA)

-

Road Haulauge Association (RHA)

-

British International Freight Association (BIFA)

-

and smaller special interests trade associations, such as the Fresh Produce Consortium, which claimed that the produce industry way losing 2 million pounds a month in spoiled goods in 2015 from break-ins around Calais.

There are also trade unions, such as:

-

Fédération nationale des transports routiers (FNTR) or

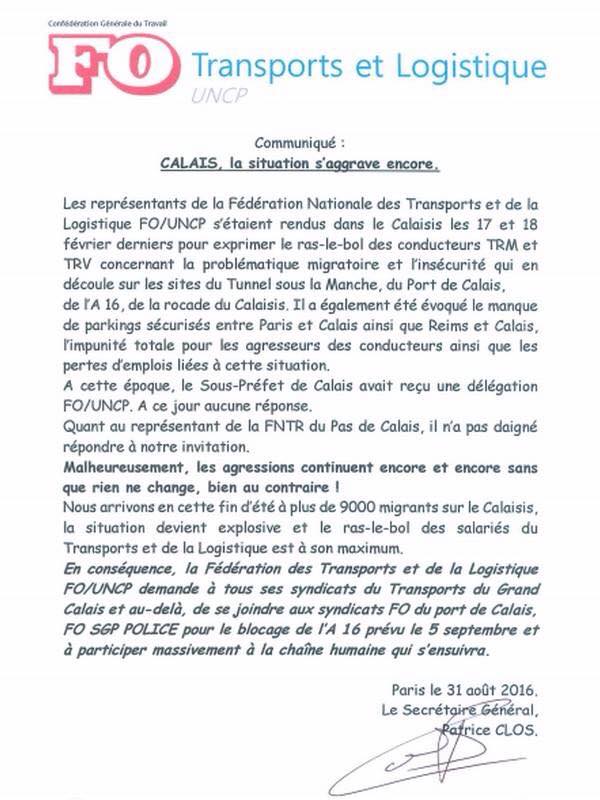

Image: FO Communique calling for anti-jungle blockade on 5 September, 2016

The president of FNTR is David Sagnard, who is director of Transports Cartier (62), a Calais-based logistics company.

These unions were involved in organizing anti-migrant demonstrations and blockades including that on Sep. 5, 2016 demanding government intervention against the camp. During Sarkozy’s brief visit in Calais in the lead up to the 2016 full eviction of the jungle, he met with the Grand rassemblement du Calaisis and representatives of FNTR and RDV.

Lorry drivers also self-organize on social media, in part sharing stories of break-ins or experiences in Calais and calling for the eviction of the camp, among other things, e.g. in the group Calais Routiers Sécurité.

FNTR is part of the Collectif des entreprises et commerces du Calaisis, an allegedly ‘apolitical’ group of 200 businesses which organized the ‘Mon port est beau. Ma ville est belle.’ protests. The protests took place in both Calais and Paris, calling for more employment for Calaisians and less migrants. They were instigated by a 2016 case where about 40 migrants tried to board a ferry in the port. The president of the collective is Frédéric Van Gansbeke, who is also president of l’Union des commerces du Calaisis and director of several Calais businesses, Fal’loisir, Fema Distribution, and Le Coin du Pain Calais.

Motivations

As a vulnerable route connecting the UK to the vast network of trade across the EU and beyond, when problems arise there, Calais can become a choke point in the flow of trade. In the ‘just-in-time’ organization of logistics, even delays of a few minutes can cause systemic delays and costs. The freight industry is therefore highly invested in the situation in Calais. Road haulage associations like the FTA and the RHA frequently push for meetings with the UK and French governments and attempt to push their perspective in the media and otherwise ensure that the freight industry can move its vehicles smoothly through Calais.

One example of the kind of systemic problems for the freight industry that can be caused by backups in Calais is the SCOP strike that took place in summer of 2015, in which workers on the MyFerryLink ferries previously operated by Eurotunnel protested over job losses and barricaded the highways with burning tires. This strike was of huge concern to trade associations representing the freight industry. The Freight Transport Association (FTA), whose members operate more than half of the UK fleet of lorries, claimed in the media that the strikes were causing the UK a loss of £250m in trade each day, along with £750,000 in added costs to the freight industry from delays and spoiled loads.

The logistics industry’s concern over Calais can also be seen in industry ‘risk analysis’ documents by groups like BSI’s supply chain service and solutions, who dedicated a special publication to Calais called ‘Calais Migrant Crisis: Impact on Cross-Channel Trade in Europe‘.

Activities in Calais

- Negotiations with the UK and French Governments

Representatives of the freight industry have met with government officials in meetings such as the ‘Pan-European Freight Security and The Migrant Crisis’ conference in 2016, where freight industry representatives, James Brokenshire, UK MPs, French and British Police, Eurotunnel and the Calais port came together to discuss increasing ‘security’ in Calais.

More recently, the FTA expressed its support for the evictions in Calais. In early 2016, the FTA pushed a ‘five point action plan for Calais’, later noting that the governments’ actions, including evicting people around the highway, echoed their own proposals. They again celebrated the October 2016 eviction and the fact that Hollande’s decision to destroy the jungle reflected their suggestions.

- Accreditation scheme to avoid fines through security protocols

Freight industry trade associations have also encouraged the introduction of technology for self-policing lorries (CCTVs, CO2 detectors, etc.) in the hope that, as compensation, the UK government will agree to drop their currently expensive fine system for companies in compliance with security recommendations. The FTA, RHA, BIFA, and other freight industry groups have expressed their public support for the UK Border Force Code of Practice and Accreditation Scheme. BIFA explains the accreditation scheme in a presentation on what it calls the “clandestine entrant regime”: Compliant hauliers, who conform to advised security practices, such as checking seals, locks, and other parts of the truck at each stop, and who otherwise collaborate with the UKBF are to be rewarded with reduced liability and a possibility to avoid fines. This seems to include to at least some extent contributing to the UKBF’s intelligence gathering. As of September 2016, BIFA reported some 450 companies had been accredited since the scheme was re-launched in Summer 2015.

- ‘Operation Stack’

Large-scale manoeuvring is required to keep trade flowing when any form of blockage occurs at key transportation nodes, even if only for an hour. ‘Operation Stack’ is the name given to a procedure that is implemented by the Kent Police and the Port of Dover to keep traffic flowing in times of disruption by ‘stacking’ lorries on the motorway, effectively turning the M20 into a giant lorry park. Operation Stack has, so far, had four different phases involving implementation on different sections of the M20. The first three phases can accommodate some 3,000 lorries. Lorries are released from the queue in blocks, allowing drivers to take longer rests during the wait, which may exceed 12 hours, instead of slowly inching along the motorway.

On 24 June 2015, in response to the industrial actions taken by SCOP ferry workers, Phase 4 of Operation Stack was implemented for the first time in its history, creating space for a further 1,600 lorries. The M20 had initially been cleared by 4 July but Operation Stack was implemented again intermittently throughout much of July 2015 to respond to industrial action as well as migrant-organized actions. Though the system had been used on average some 4 times per year over the first 20 years of its existence, over the summer of 2015 alone, as a result of events in Calais, it was implemented 32 times. Congestion throughout Kent caused significant discontent among locals. Damian Collins, MP for Folkestone and Hythe, complained that the Kent County Council was ill-equipped to respond to the scale of the situation. Talks were eventually opened with Home Secretary Theresa May and a larger scale response was initiated. Subsequently, plans were hastily made for a controversial £250 million lorry park in Stanford West, to be partially operational by summer 2017.

Relations to other key actors

UK and French Government

While the government generally shares the freight industry’s goal of keeping trade flowing at all costs, groups like the FTA have come into conflict with the UK government over the responsibility they place on logistics companies for enforcing the border. Lorry drivers can be held responsible for ‘stowaways’ found on their trucks with a fine of up to £2,000 per person found; according to the FTA, the freight industry received £6.6m in such fines in 2014.

Kent Police

Eurotunnel and Port (relies on freight industry)